A workflow for grading and assessment in Google docs

In 2002, I stopped accepting papers and began requiring all students to send me their writing by email. Over the following decade, I developed and continually tweaked a workflow through which I corrected errors, responded to ideas, and made suggestions for stylistic improvement using Microsoft Word's editing and commenting tools. In my comments, I also incorporated hyperlinks to the writing guide that my colleague Celia Easton and I had thrown up on the web — using Netscape Composer for the first iteration — a few years earlier.

When Google introduced Drive in 2012, I modified my workflow by asking students to drop their Word files in a shared Drive folder. I offered them the option to share a draft and used Google's comment feature to give them some feedback. But I continued to mark up the essays in Word and return them by email. I began providing a completed rubric form as well, the byproduct of my dozen or so years' involvement with institutional assessment.

My workflow changed again — dramatically — when, in 2014, my institution adopted Google Apps for Education. Suddenly it was a simple matter to create a shared, flexible workspace for collaboration, and, in doing so, to bring the whole academic writing process — from initial brainstorm to evaluated final draft — closer to the form that we implicitly aspire to when we write in the margins of student work. It's the same form I tell my students to aspire to in their own compositions, because it's the form from which academic writing, if not all writing, emerges: the form of conversation.

Here's what that process looks like for me right now.

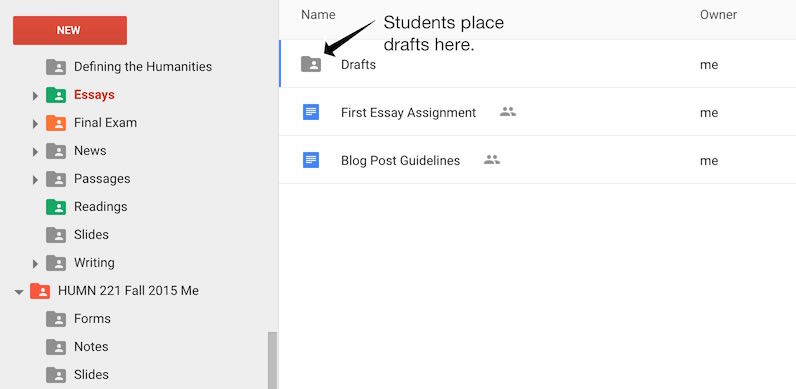

Inside a folder that I share with the entire class, I create another shared folder titled Essays. If students are writing two papers over the course of the semester, Essays holds separate shared folders for First Essay and Second Essay.

First Essay holds a shared document containing the assignment and another shared folder titled Drafts. I invite students to leave comments on the assignment. If they email me with questions, I tell them I'll only answer their questions in the document itself, where everyone can see my answers. Whereas private queries from students by email can come to feel like a nuisance, I'm always happy to have a conversation about the objectives and terms of an assignment, and marginal comments in the assignment itself are the perfect place to hold that conversation.

Each student creates a document in Drafts in which to carry out the drafting process in stages, from initial brainstorm to a first complete iteration of the essay. I invite them to look at and comment on one another's drafts as these grow. I also ask them to do a bit of metacognitive work by leaving comments on their own writing. For example, if their opening paragraph is supposed to have a they say component and an I say component — after the model championed by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein — I ask them to highlight these components and identify them. I also ask them to explain which of the several types of I say strategies they've adopted. When their drafts are farther along, I ask them to identify those places in the draft where the "skeptic's voice" can be heard, and what kind of answer they've provided. I may reply to these metacognitive comments even before I weigh in on anything in the draft itself.

As they draft, my students can send me an email from inside the document whenever they have a question about their progress by using File > Email collaborators and de-selecting everyone but me from the list. If the timing is right, a student and I may find ourselves inside the student's document together, and rather than leave a marginal comment, I may hit the "Chat" button and make the conversation live. Skeptics will say that this online conversation is impersonal compared to a face-to-face chat in office hours, but if it saves both of us the time and headache involved in scheduling a meeting (obstacles that might prevent the student from coming in to begin with), and if it gets the student out of a blind alley and onto a decent path forward right now, in my view it's more than worth the sacrifice of personal immediacy. Nor does it preclude an in-person conversation later on if either of us wants to follow up.

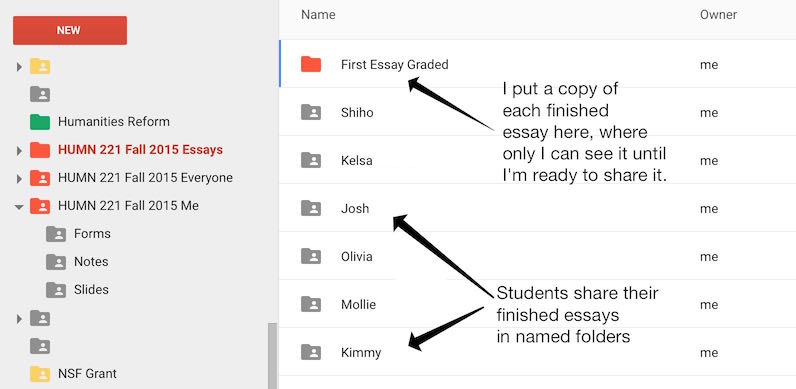

When the time arrives for students to call their work "finished," I ask them to put clean versions of their essays in folders I've created and named for them. My Jane Roe, folder, for example, is shared by Jane and me alone. All the students' individual folders live inside a folder on my Drive to which I alone have access, which helps me to keep things neatly organized. A mind-bending and wonderful feature of Drive is the ability to put a file or folder with wider permissions inside a folder with narrower ones. So a folder to which I alone have access can contain a folder to which I and another have access, and that folder, if desired, can hold a file that's visible to anyone on the web.

I require the students to include metacognitive comments in the finished version, just as they did in the draft.

At this point I could dive into evaluating the essays, but I don't. I might get interrupted in the middle of working on a document, and the last thing I want is for the student to pop in, see a bunch of comments, and be left to wonder what grade the comments might portend. In addition, all the documents need to become stable at this point; it wouldn't be fair to let John continue making changes to his document after I've evaluated Jane's.

So I do the same thing I used to do when I took in student work by email. I make a copy of the original, rename it, and put my comments there. Since the copy is in a shared folder, I have to either remove the student's access to it temporarily or — my preferred method of work — move it into a new folder within Essays that's not shared. Remember, Essays itself isn't shared — only Jane Roe, John Doe, etc. — so by default any new folder I create within Essays — e.g., First Essay Graded — is visible to me alone.

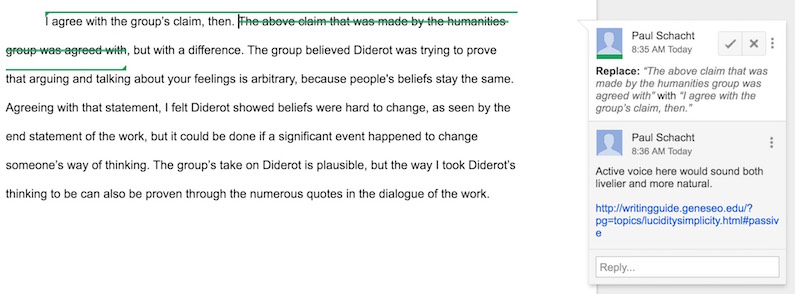

I've developed a few protocols for commenting in Google docs. I turn the editing mode (menu under the pencil icon at the document's top right) to Suggesting so that the student can easily see how I've altered sentence structure, wording, or punctuation. If I think a change of this kind requires elucidation, I provide it in a reply to the comment that's created by the proposed change. If I've deleted a word because it's redundant, I can simply type "redundant" as my reply. I can also include a link to the Geneseo writing guide's discussion of Wordiness and Redundancy. (I've created shortcuts for typing many of these links using TextExpander, but that's a topic for another post.)

To leave a comment on the student's argument, or to make a more general suggestion about style/organization/etc., I highlight a bit of text and add a comment about it. (Using keyboard commands for this is much faster than navigating the menus. Select some text and — on a Mac — hit Command-Option-M to opens a comment box. After typing the essay, hit Control-Enter to save.)

A nice feature of Google doc comments is that you can toss in some markdown-like styling. For example, adding an underscore (_) on both ends of a text string in your comment will cause it to be formatted in italics once you save. Adding asterisks (*) will cause the text to appear bold.

When I've finished evaluating the essay, I share it with the student. The student can now review it and — I take pains to advertise — reply in the margin to my comments. We can keep the conversation going to help clarify a point of grammar or usage, discuss an interesting idea, or think further together about the essay's structure. The ease with which you can make the margin of a document a space for bilateral (or even multilateral) conversation, rather than unilateral (instructor-to-student) instructions and animadversions, is one big advantage of using Google docs rather than Word.

Perhaps a couple of quick follow-ups in the margin can obviate a longer, less focused meeting over the essay's grade. Perhaps an extended conversation about an interesting idea will lead to an appointment or a visit during office hours to explore the idea in depth.

In my grade-with-Word days, and even for a short while after transitioning to Google docs, I put a summary comment and the student's grade at the bottom of the essay, just as I'd done for many years grading with pen and paper. Now, however, I put that comment in a brief online form that I complete for every essay I evaluate. This form is the point of intersection between the student's metacognition, my evaluation, and assessment.

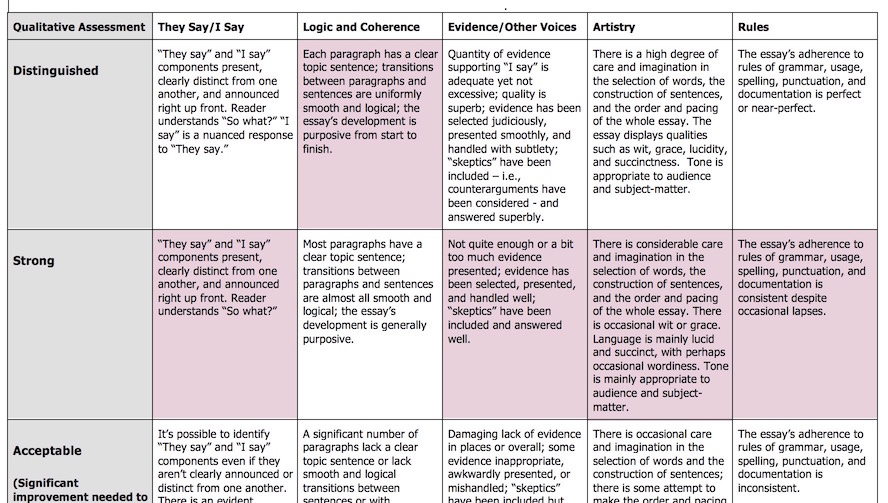

Remember the rubric I used to share with students? That was a table I'd created in Word and turned into a template; I would create a new document based on the template for each essay graded, highlight the cells as you see above, and send it to the student with the essay. Now, instead, I create a Google form like the one below and complete it for each essay I grade.

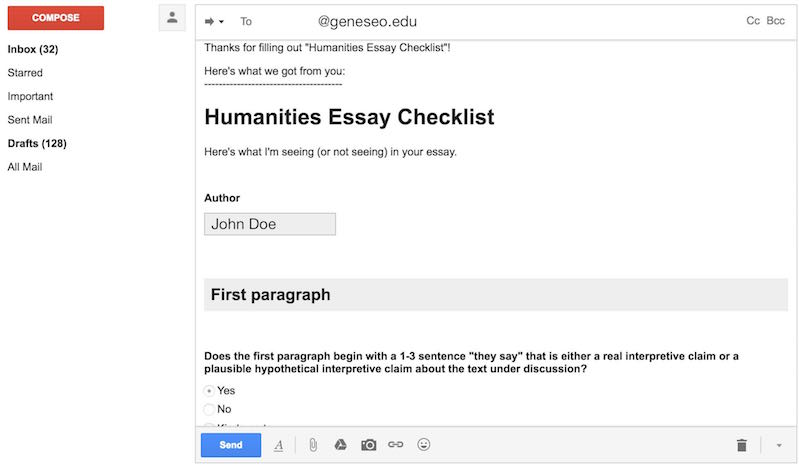

Because Geneseo has implemented Google Apps for Education, I can set the form to collect the respondent's email address. (You won't see that option in the form above because it's a replica of the form I actually use, with permissions changed to make it visible beyond SUNY Geneseo.) Why would I collect the respondent's email address when I'm the respondent? Because now, at the bottom of the form, I can check a box to have my responses emailed to me. I can then forward each of these emails from my inbox to the appropriate student, providing that student with feedback tied directly to the assignment's requirements that includes a global comment and a grade. (Emailing is easy because our implementation of Gmail is tied into our campus directory, so as soon as I start typing a name in the To field, the student's address comes up.)

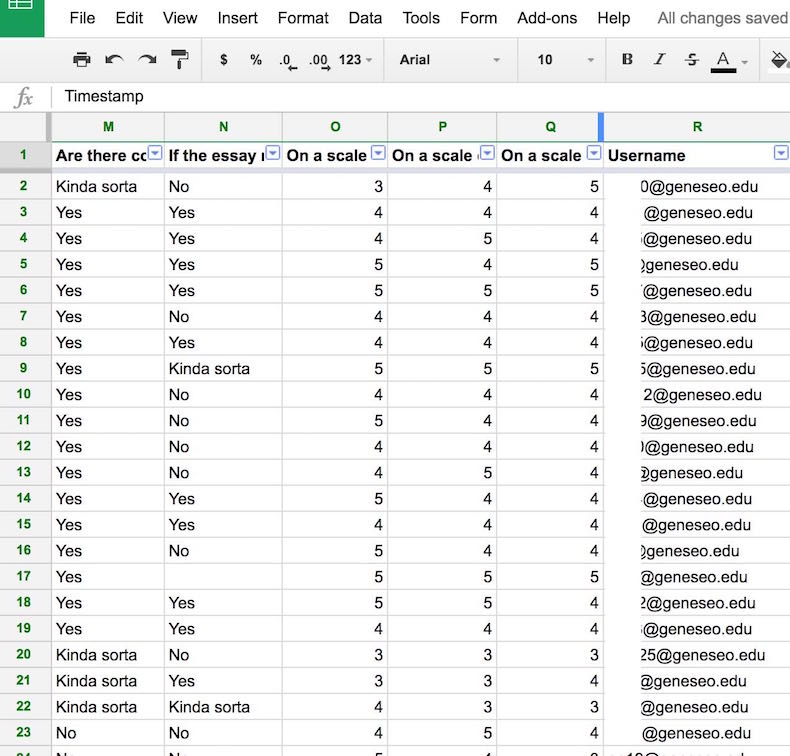

Best of all, once I've emailed everyone, I have a snapshot of how well the class as a whole met my requirements in a single spreadsheet that also includes all the students' grades and all my global comments.

The alignment between my form and the students' own comments in their essays provides a link between my evaluation and their metacognitive work, but I tighten that connection further with a step I haven't mentioned yet. It takes place at the point where the student shares the essay's "final" version. I require the student to complete, just before sharing, a self-evaluation in a form much like the one I will use for my own evaluation.

If, on the form, they say they've included a they say, it's likely, after all their metacognitive work, that I'll also say they included a they say.

I know what you're saying to yourself at this point: Rube Goldberg. To which I say: Nolo contendere. A machine you create never seems as complicated to you as it does to others, especially once you've had it running smoothly for a while. But this machine certainly has a lot of moving parts. Of course, to suit your own needs and tolerance for complexity, you can re-arrange them, re-connect them in different ways, or even leave some out.

In any case, here's a quick summary of the workflow:

- Create a folder in Drive for your class with a name like ENGL100 F16.

- Inside ENGL100 F16, create two subfolders, ENGL100 F16 Everyone and ENGL100 F16 Finished Essays.

- Share ENGL100 F16 Everyone with your class.

- Don't share ENGL100 F16 Finished Essays with anyone.

- Inside ENGL100 F16 Finished Essays create one folder for each student, using the student's name as the folder name. Share the folder bearing the student's name with that student alone.

- Inside ENGL100 F16 Everyone, create Essays.

- For the first paper, inside Essays create First Essay. Put your description of the assignment here in a doc.

- Repeat, if desired, and modify accordingly, for essays 2 through n.

- Inside First Essay, create Drafts, and have your students put their drafts here. They can create them as Google docs inside the folder, create them elsewhere and move them into the folder, or upload to the folder Word documents that you can later convert to Google docs.

- Talk to them about their drafts inside their drafts, using comments and chat. Metacognition optional.

- Have each student put the finished essay in the folder bearing the student's name. The student can use this one folder for papers 1 through n.

- Create a copy of each essay that you alone can see. (Right-click on the file icon and select Make a copy.) Either remove the author's viewing rights or move the essay to a folder not shared with anyone. For example, you might create First Essay Graded inside First Essay, where it would appear in the list of folders named for students.

- Suggest edits and put comments in the margin of each student's essay. When done commenting on an essay, share the essay with the student.

- You're done grading, but if you'd like to strengthen the connection between your grade and your essay requirements, you can also create a Google form, set it to collect the respondent's email address, populate it with questions that review whether the essay has met the requirements, fill it out for each essay you read immediately after reading, checking the box to have a copy emailed to you after submission, and forward the forms in your inbox to the students themselves.

- If you want to encourage even more metacognition, you can create a form that you require the students themselves to complete before submitting each essay.

If you're already using a workflow similar to this, or think you have a better one, or have suggestions for improving this one, I hope you'll let me know in the comments.