CSS Basics

Cascading Style Sheets—CSS for short—provide a powerful means of formatting the content of an HTML document or even an entire website. By separating formatting specifications from our markup, we gain the ability to make global adjustments to the appearance of our web pages without having to alter the markup itself.

Why “cascading”? Because we can specify formatting at multiple removes from the markup to be styled. Style rules that are closer to the affected markup supersede rules at the next-farthest remove, and so on up the hierarchy. As a result, we can specify a set of global rules that will govern multiple documents, fine-tune these rules as needed for a particular document, further tune those document-level rules for particular sections of a document, and, finally, override rules at any of these levels with specific rules attached to a single element in one location within the document. In addition, we can specify how content within a particular element—say, <p>—will be formatted in different contexts by defining different style classes. Content in a <p> that belongs to one class (assigned to it using the class attribute) will then appear different (in color, size, font, or any combination of these and other features) from content that belongs to another.

At each level of the cascade, if we want to make adjustments to styles set at the level above, we need only specify what will be different from that level; the other style rules will still hold.

Setting styles for a page

Let’s begin by looking at how we might use CSS in a single web page. To do this, we’re going to create a new practice file inside ~/critical-digital. Use the text-editor of your choice to create the new practice file; if you’ve installed VS Code and its command-line tool, you can simply navigate to ~/critical-digital and type:

code practicing-stylesheets.html

Once the file opens in VS Code, save it before going any further. Then paste the following into the file:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Practicing with Stylesheets</title>

<style>

body {

background-color: black;

}

h1 {

color: red;

font-family: verdana;

}

p {

color: white;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Practicing with Stylesheets</h1>

<p>This is an HTML document with one sentence.</p>

</body>

</html>

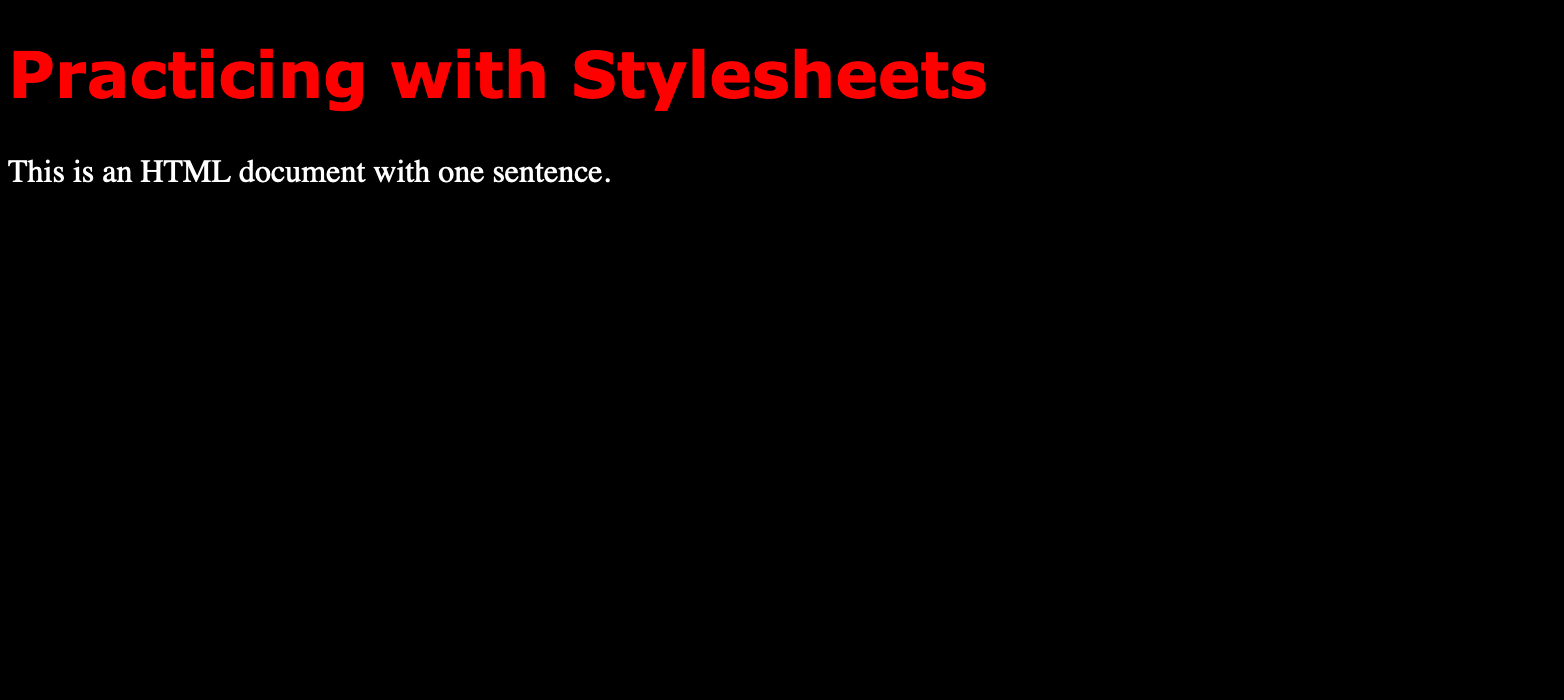

Save again, then open practicing-stylesheets.html in a browser. You should see this.

Notice that the visible content of this file is marked up with HTML elements that you used in your earlier practice file: <body>, <h1>, <p>. Those tags don’t say anything about what font should be used for these elements, what color the font should be, or what the body’s background color should be. That information is all contained within <style>, which lives inside <head>, where it’s a sibling of <title>.

Of course, the body of your earlier practice file had a background color (most likely white), and your level-one heading and paragraph text had color (most likely black) and were in a particular font (most likely some version of Times). In the absence of style information set by you, the browser simply uses its default style settings.

Imagine if you did have to specify style information, such as font and color, inside every <p> element of a document containing even just a dozen or so paragraphs. And imagine having to go into every one of those <p> elements if you decided, at some point, that you wanted all your paragraph text to be in, say, Gill Sans rather than Verdana, and some light shade of gray rather than white. It would be a lot of work, and you’d be bound to make a mistake somewhere, such as missing one of the paragraphs.

Using the syntax in our example (which will be explained in a later section), you can set styles for the other elements you used in your earlier practice file—such as <img>, <tr>, and <li>—and a great many more.

But suppose you want all but one of your paragraphs to be white, and that one exception to be bright green? You can do that by setting an inline style for that one paragraph which will override the one set document-wide in <style>. That capacity to override at each level of the hierarchy from site to document to element is, again, what makes style sheets “cascading.”

Setting styles inline

Back in your new practice file (practicing-stylesheets.html), let’s add a few more paragraphs. Paste the content below into the file.

<p>The artist is the creator of beautiful things. To reveal art and

conceal the artist is art’s aim. The critic is he who can translate

into another manner or a new material his impression of beautiful

things.</p>

<p>The highest as the lowest form of criticism is a mode of autobiography.

Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without

being charming. This is a fault.</p>

<p>Those who find beautiful meanings in beautiful things are the

cultivated. For these there is hope. They are the elect to whom

beautiful things mean only beauty.</p>

<p>There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well

written, or badly written. That is all.</p>

<p>The nineteenth century dislike of realism is the rage of Caliban seeing

his own face in a glass.</p>

Let’s change the font color of that second-to-last paragraph. Edit it as follows, using the style attribute to specify the different color:

<p style="color:greenyellow;">There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.</p>

Save the file and refresh your browser. You should see that bright green color applied to the second-to-last paragraph alone.

Again, the syntax for defining styles at every level will be covered in a later section.

Setting styles site-wide

Changing styles for the text in a dozen paragraphs within a single web page would be tedious enough. Now imagine re-styling paragraph text for perhaps hundreds of paragraphs across multiple pages. For this task, we’re helped not only by the separation of styles from HTML markup but by the ability to separate style rules from the document(s) to which they apply.

The web’s defining affordance—the hyperlink—makes this separation possible. We simply put our style rules, written in the same syntax we used to style a single document, in their own file. Then we link to this file from every document we want to be governed by its rules. The link in this instance isn’t one your user clicks on; rather, it’s one that tells the browser where, on the web, to find the file containing the style rules.

The link can point to a file on the same server hosting your website, but it can just as easily point to a URI living on another server.

Inside your ~/critical-digital folder, create a new file named styles.css. (This will be a plain text file. The .css extension enables your operating system or browser to recognize that the text inside it is written in CSS syntax.)

From practicing-stylesheets.html, cut the style rules inside the <style> element and paste them into styles.css. (Cut them, don’t copy them, so that you’re leaving the <style> element empty.)

Inside <head>, above <style>, paste the following:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="styles.css" />

The entire top portion of your practicing-stylesheets.html should now look like this:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Practicing with Stylesheets</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="styles.css" />

<style>

</style>

</head>

Meanwhile, your entire styles.css document should look like this:

body {

background-color: black;

}

h1 {

color: red;

font-family: verdana;

}

p {

color: white;

}

Be sure that you’ve saved both files. Now, open practicing-stylesheets.html in a browser. (If it’s already open, just refresh the page.) The page should look no different from how it did earlier. Why would it? Your style rules haven’t changed. But they’re no longer contained inside practicing-stylesheets.html (except for the one inline style we added to a single paragraph); instead, they’re being pulled in via the link you added in <head> to your external styles.css file.

At this point, you could cut the empty <style></style> element from practicing-stylesheets.html. However, take note: If your external file specifies files across multiple documents, but you want to customize something for just this one document, any styles you put within <style></style> would override those in the external file for this one document alone, just as any inline styles you specify using the style attribute within a particular element will override those set within <style></style> for that one element alone. That’s the cascade at work.

Go ahead and play with the styles in your external file to see how changes you make there will affect practicing-stylesheets.html. Remember that the changes will only be visible after you (1) save them in styles.css and (2) refresh practicing-stylesheets.html in your browser. Notice that you needn’t make any change to practicing-stylesheets.html itself for the document to display the new styles you set in styles.css.