What is the Web?

We’ve previously described the web as “a layer built on top of the internet.” Let’s look more closely at when and how that layer was built, and how it functions today.

Pre-history

If the internet is a network of networked computers, we can think of the web as a network of the information that lives on those computers. Communication protocols link computers on the internet. What links information on the web? Well, basically, links—or, as they were originally, and are sometimes still, called: hyperlinks.

The concept of information linked in a decentralized network is much older than the web you access on your computer—formally known as the “World Wide Web.” In print documents, for example, footnotes and bibliographical references have long served as pointers to related information sources, which, if followed, might lead to other sources, in a chain of referrals that in principle could go on indefinitely. What’s distinctive, historically new, and arguably magical about the World Wide Web is its use of a software interface to let you jump directly from one information source to another with a simple gesture, such as a mouse-click or finger-tap.

But even the idea of linked computer documents pre-dates the web. In the 1960s, Ted Nelson coined the terms “hypertext” and “hypermedia” to denote linked document and media nodes, and in 1968, at a computer conference in San Francisco, Douglas Engelbart gave what has come to be known as “The Mother of All Demos” to show how his oN-line System (NLS) made it possible, among other things, to navigate among linked documents.

Nelson’s and Engelbart’s names are mentioned frequently in histories of the web. Less often mentioned are the names of women who contributed to hypertext projects, particularly during the 1980s, women like Wendy Hall, whose team developed the Microcosm hypermedia system at the University of Southampton.

As Claire L. Evans explains in Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet (Penguin, 2018):

The most famous hypertext pioneers are men—Doug Engelbart…Ted Nelson…but the Web appeared on the scene only after hypertext principles and conventions had been explored for nearly a decade by brilliant female researchers and computer scientists.…Hypertext is, in many ways, the practice of transforming pure data into knowledge. And like programming a generation earlier, it was where the women were. (154-155)

In exploring why women in computing would be drawn to hypertext, Evans also illuminates how the concept helped move computing as a whole from the province of engineers, mathematicians, and scientists to the larger domain of researchers and scholars across the natural sciences, social sciences, arts, and humanities, and, ultimately, to the entire realm of an information-hungry general public. What the developers who worked on early hypertext systems shared “was a humanisitic, user-driven approach. To them, the final product wasn’t always software: it was the effect software had on people” (162).

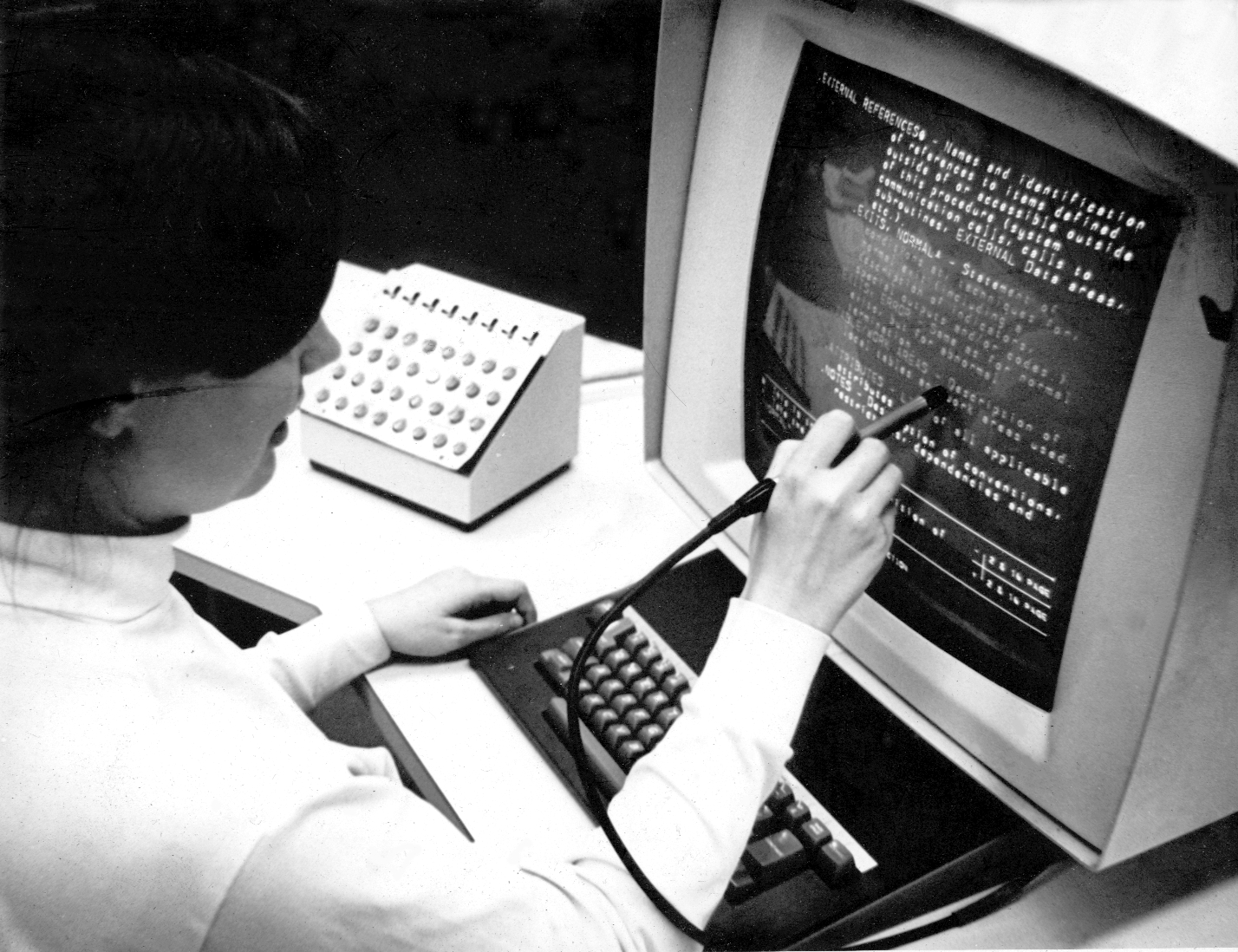

The Hypertext Editing System (HES) console in use at Brown University, circa October 1969 Gregory Lloyd, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Hypertext Editing System (HES) console in use at Brown University, circa October 1969 Gregory Lloyd, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Birth of the web

Early hypertext systems focused on establishing links among documents stored on a single computer. A prominent, commercially successful example was Apple’s HyperCard system, released for its model IIGS computer in 1987, which enabled users to navigate by mouse-click among related virtual cards holding various types of editable information.

But such systems were inadequate to the needs of a large research community collaborating in a networked environment, with different users needing to access the same documents. One of these was the particle physics community. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee, while a fellow at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (known as CERN), collaborated with colleague Robert Cailliau to circulate a a proposal for information management based on the idea of hypertext. Working on his personal NeXT computer, Berners-Lee wrote a software application that he called “WorldWideWeb,” which included a browser for both reading and editing documents. Berners-Lee also developed software that enabled a server to deliver (“serve”) these documents to a connected computer.

Though initially met with some skepticism, Berners-Lee’s web idea caught on, not only within CERN but beyond. It wasn’t inevitable that it would. There were competing networked file-discovery and file-sharing solutions; as the 1990s began, one of these, Gopher, developed at the University of Minnesota, looked like it might well be the face of the internet’s future. (At the independent journalism outlet Minnpost, Tim Gihring published a succinct account of “The rise and fall of the Gopher protocol” in 2016.) But WorldWideWeb had at least two decisive advantages. For one thing, it enabled connections to grow organically, as users added more links to existing pages and more pages with links to other pages. By contrast, Gopher’s links were curated in hierarchically arranged menus.

For another, CERN decided to put the source code of WorldWideWeb in the public domain, releasing it in April 1993 for the world to use free of charge. The University of Minnesota, on the other hand, sought to monetize Gopher by charging licensing fees to users.

Later in 1993, the National Center for Supercomputing Applications released a version of its web browser Mosaic that could be installed on personal computers running either Apple’s Macintosh operating system or Microsoft Windows. Its ease of installation and ability to combine images with the text in web pages helped increase the web’s popularity and spurred the development of other browsers. The web quickly became the internet’s dominant information-exchange medium.

The web’s rapidly expanding popularity led to a period of intense competition among browser developers, sometimes known as “the browser wars”. Developers’ efforts to gain competitive advantage by including proprietary functionality in their browsers threatened the principle of interoperability that was, in some sense, the whole point of the web as Berners-Lee had conceived it. Ultimately, though, a standards-based approach prevailed, making possible the broad freedom to interoperate that users enjoy when using the web today.

Future of the web

On the occasion of the web’s 20th anniversary in 2010, Berners-Lee authored “Long Live the Web: A Call for Continued Open Standards and Neutrality” for the journal Scientific American. Although the web has now passed its 30th anniversary, Berners-Lee’s main points remain highly relevant. Thanks to its basic architecture and its use of free and open standards, the web has been, and continues to be, a great equalizer and a powerful force for democracy, social connectivity, and coordinated political action. But the web’s openness is under constant pressure from both commercial interests and governments. All of the threats Berners-Lee mentions are still with us: surveillance, censorship, appification of interfaces, commodification of users through data profiling and targeted advertising, attempts to undermine or abolish net neutrality.

In addition, the years since 2010 have increased awareness of threats that Berners-Lee doesn’t mention, such as harrassment, hate speech, and the viral spread of misinformation. Our ability to maintain the web’s democratic potential will depend not only on resisting efforts to reduce its openness but on finding ways to counteract some of the adverse effects of openness itself.