IIIF images

Many manuscript images are available on the web using a standard called the “International Image Interoperability Framework,” or IIIF for short.

When images adhere to this standard and are served from a IIIF server, users can do more than simply point to them. It’s possible to bring a IIIF-compliant image into a web page or other application in a way that re-sizes the image, crops it, rotates it, or performs some other action.

You perform these actions by following the protocols for the IIIF API. “API” is an abbreviation for “Application Programming Interface.” APIs enable web applications to interact with each other. You may not have seen the term before, but you likely make use of APIs regularly. The APIs for Google’s web applications enable these applications to “talk to” each other and to other applications, so that, for example, Slack can display your Google docs or your email can display the details of an airline reservation you recently made. APIs make possible the popular web service If This, Then That, which offers API-based “recipes” that enable you to do things like get NASA’s image of the day in your email, send yourself an email with the location where you parked your car or save tweets with a hashtag you pick to a Google sheet.

Let’s take a look at the different ways you can display a manuscript image using the IIIF API, taking the Walden manuscript as our example.

Calling an image at full size

Type the following address (also known as a “URI”) into your web browser’s location bar and hit Return or Enter:

https://cdm16003.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/iiif/p16003coll16/8/full/full/0/default.jpg

It will take some time for the image to load, especially if you don’t have a high-speed internet connection. High-quality scans of manuscript images have large file sizes so that researchers and other users can examine them in fine detail. The image you’ve just loaded is 7.4 MB. It’s 6751 pixels wide by 9000 pixels long.

Your browser probably loaded a scaled-down version of the image so that the entire image would fit on your screen. If you mouse over the image, you should see an icon of a magnifying glass with a “+” sign inside it. Clicking on the image should enlarge it to full size, so that you can see it in great detail. In most browsers, you can step down the size of the image using the keyboard combination Ctrl + - (Mac: Command + -). Similarly, you can step it up using Ctrl + = (Mac Command + =) You can save the image to your own computer by right-clicking and choosing “Save Image As …” or the equivalent.

The size of high-quality scans is one reason the IIIF standard is so important: if you had to use all these images at full size in your project, your users would spend a lot of time drumming their fingers, waiting for your images to arrive on their screens.

Calling an image at a percentage of its original size

The URI you entered in your browser’s location bar above should have (eventually!) delivered the first page of the “A” version of Thoreau’s Walden. What if you wanted to call the image at a specified fraction of its original size so that it would load much faster?

You could do that by replacing the original URI you typed with the following:

https://cdm16003.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/iiif/p16003coll16/8/full/pct:10/0/default.jpg

When you hit Return/Enter, the image should load much, much faster. This image is 870 x 1160 pixels, with a file size of 136 KB — just under 2% of the original’s size.

How do the two URIs differ? You have to look closely to see. Start at the end (…default.jpg) and trace your way back till you see this: /full/pct:10/ Compare with the URI above, which reads, at the same location, /full/full/. The second URI delivers the image at 10% of its original size.

We can bring the reduced-size image into the present page by typing

, and it will be displayed as below:

URI syntax

There’s a regular pattern to the IIIF URIs, as explained on this page explaining the IIIF URI syntax.

The basic template looks like this:

{scheme}://{server}{/prefix}/{identifier}/{region}/{size}/{rotation}/{quality}.{format}

In the URIs we’ve been looking at,

{scheme}= https{server}= cdm16003.contentdm.oclc.org{/prefix}= /digital/iiif{region}= full{size}= full (first URI) or pct:10 (second URI){rotation}= 0{quality}= default{format}= jpg

For our purposes, what matters most are the following bits of the URI:

- region: In both examples, the image displays the full two-dimensional extent of the image, rather than a limited section of it.

- size: In the first example, the image is displayed at its full size. In the second, it’s dispalyed at pct:10 (i.e., 10%) of its full size.

- rotation: In both examples, the rotation is 0. We could replace

0with90,180, or270to rotate the image clockwise by the corresponding number of degrees.

Displaying a page section

To display a section of an image — in other words, a region other than full — you can specify the coordinates of the section by replacing full with x,y,w,h where

x= the number of pixels from the 0 position of the horizontal axisy= the number of pixels from the 0 position of the vertical axisw= the width of the region in pixelsh= the height of the region in pixels.

(Note that the x,y coordinates 0,0 represent the upper left corner of the image, and that the upper left corner of the image is not the same as the upper left corner of the manuscript page, since the gray margin surrounding the page is part of the image.)

So to display the bracketed and canceled passage on this page, we might call https://cdm16003.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/iiif/p16003coll16/8/1150,6200,7000,2000/pct:30/0/default.jpg, yielding this:

Determining the right coordinates for a limited image region takes some finagling. If you download the image and open it in an image-viewing application such as Apple’s Preview, you should be able to get approximate coordinates by dragging your cursor over the image. You can then pop the URI-with-coordinates into your browser’s location bar and, by repeatedly adjusting them and refreshing the browser, ascertain that you’re capturing the desired region.

Rotating images

To rotate an image region, replace the 0 with the desired rotation (e.g., 90 for 90 degrees).

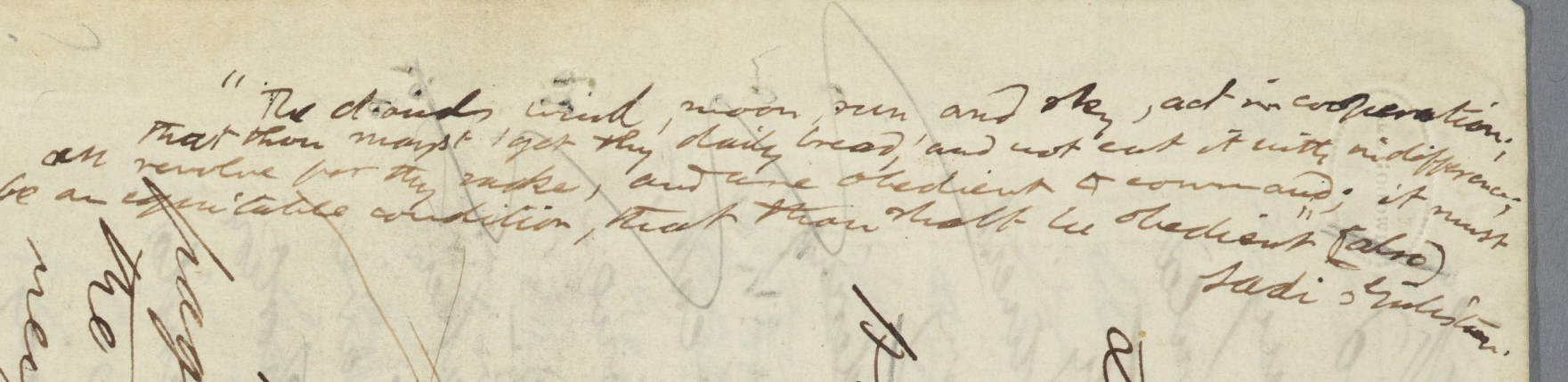

For example, the URI https://cdm16003.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/iiif/p16003coll16/434/800,737,1450,5870/pct:30/90/default.jpg will bring up the region with coordinates 800,737,1450,5870 on p. 1 of the B-C Version (xml:id hm924v3n434 in the Google sheet manifest) rotated 90 degrees at 30%, making it easier to read what Thoreau has written vertically in the left margin: